One of the most important and overlooked moments in history occurs when the last person with direct experience of an historical event dies. One of the more memorable recent examples was when Florence Green, the last veteran of the First World War died. That meant there was no one left with living memory of a war that launched the 20th century on its violent trajectory and changed the world forever. While the war officially ended 94 years before Ms. Green died, the living memory of it lasted up to her death in 2012. Only then, had the war truly become history in the past tense. There was no one left with military experience of the war. At some undetermined point not far into the future, the last civilian who had personal experience of the war would also have died. After that, everything about World War I comes to us second hand. The greatest primary historical sources known to us are gone forever. That also holds true for other events surrounding the war such as the Paris Peace Conference. That seminal event radically altered the borders of Eastern Europe. That legacy lives on today.

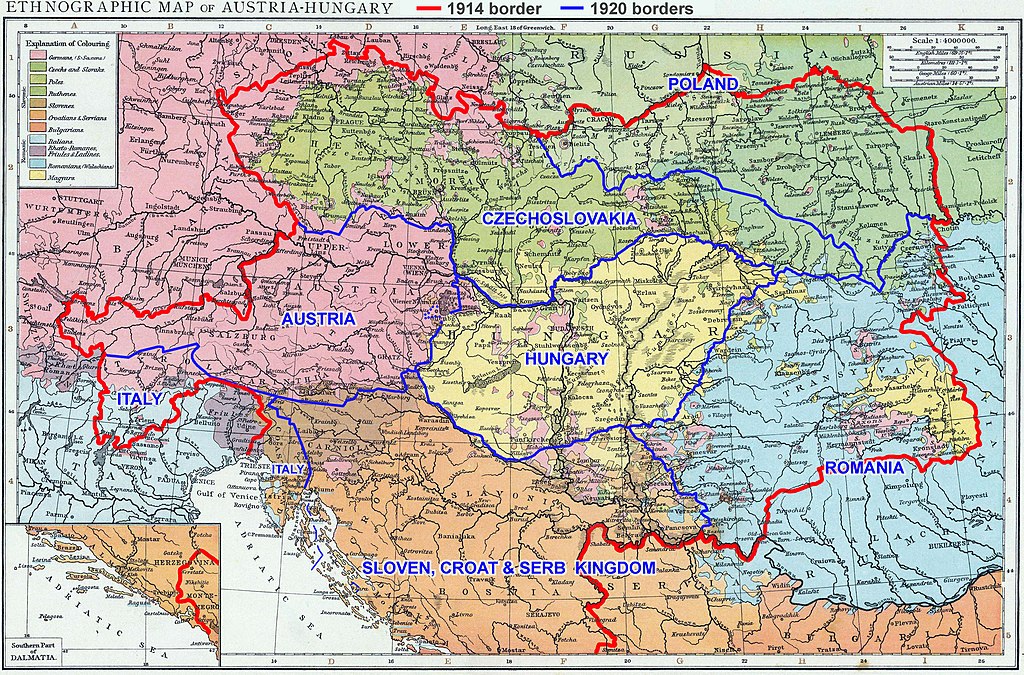

Border control – Austria-Hungary border in 1914 & 1920 (Credit: Richard Andree)

Living Link – A Lasting Legacy

You don’t know what you got until it’s gone. That is one cliché that has the ring of truth. My mentor, who was also a university history professor, told me that one of his former colleagues had been at the Paris Peace Conference as an advisor to the negotiators. He spoke of this colleague several times, always bringing up their attendance at the conference. There were no specific stories relating to his colleague’s work in Paris, but that was not really the point. Just knowing someone who had been in attendance was a source of fascination. Hearing about a living connection to such an important world historical event made the peace conference seem much closer. The usual black and white photographs found in history books communicate distance. A personal connection brings the past closer. Everything that happened in Paris seems more intriguing.

I was only indirectly linked to my mentor’s colleague, but I wanted to ask him many questions. What and who did he see at the peace conference? Did he have any idea at the time of what troubles would result from the treaties? Those questions cannot be answered because the man passed away long ago. A living link has been broken forever. Other legacies of the Paris Peace Conference are as alive today as when the treaties that resulted from the negotiations went into effect. Specifically, the Treaty of Trianon which partitioned the Kingdom of Hungary’s territory. More than any of the other treaties negotiated at the peace conference, Trianon is the one that is still controversial. I have felt the tension of that controversy when traveling throughout the parts of Eastern Europe affected by Trianon. The legacy of Trianon was the reason I planned my itinerary for the lost cities beyond Hungary’s borders.

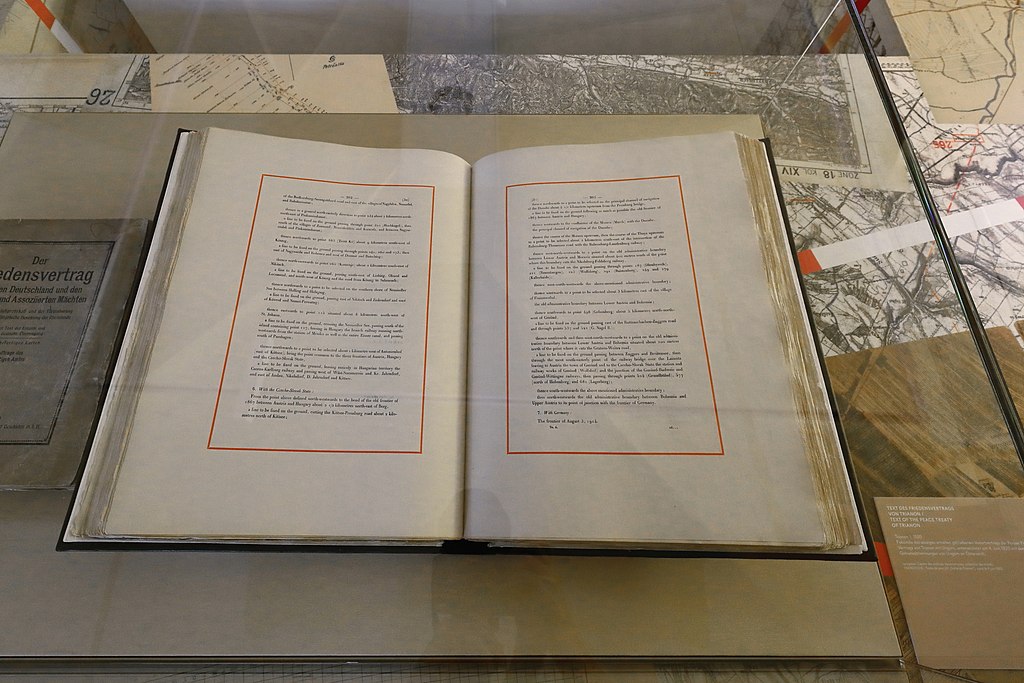

A sense of finality – Treaty of Trianon (Credit: C. Stadler/Bwag)

Obstacle Courses – Trapped by Trianon

We are not trapped within the past, as much as we are trapped by it. That is because history hems us in. We are wedded to the past and it is difficult, if not impossible, to find grounds for divorce. All the history that has ever happened created the world in which we now live. And in my case, the world in which I want to travel. This includes my itinerary for visiting the lost cities. The Treaty of Trianon’s legacy is written all over my itinerary because of borders and railway networks. For instance, planning a journey from Timisoara to Subotica turned into a logistical nightmare. One that I suffered from the comfort of an armchair in a climate-controlled home. I can only imagine how tiring the actual trip might be. In the 21st century, all the obstacles of borders, different national railway networks, and schedules that lead to increasingly lengthy travel times feel unnecessary. I have read quite a few books and articles which cover the treaty making that led to the Austro-Hungarian Empire being carved up by the victors of World War I. Very little of that reading prepared me for just how much the Treaty of Trianon’s legacy still affects travel throughout the region.

Planning a trip to visit the lost cities should have been relatively simple. Well, it was at the turn of the 20th century. Back then the lost cities were all connected with Budapest. That would not last as the nations that inherited the lost cities after Trianon hit the kill switch on parts of the Hungarian Railway Network which ran into their territories. The lines that still ran were at the mercy of border control which meant mind numbing delays. This not only hurt people, but it also dealt a terrible blow to the economies of Hungary and all the successor states as economic connections were severed. People, transport, and commodities had to be rerouted. Subotica would now look to Belgrade, instead of Budapest. The same was true for Timisoara, whose overlords were now in Bucharest. The list goes on. None of the successor states trusted Hungary and Hungary seethed with resentment. This was fertile ground for radical ideologies to take hold.

Monumental memory – Trianon memorial in a Hungarian town (Credit: Laslovarga)

Opening The Border – An Uneasy Peace

Whether the changes wrought by Trianon made any sense or not, they would have staying power. The Second World War altered them momentarily, but afterwards the borders snapped shut with a vengeance. The changes have been permanent ever since then. Only membership in the European Union has slowly pried some of them back open again. That is still not the case with Hungary and Serbia, or Romania and Serbia. Even the Hungary-Romania border still has border control. Seventeen years after Romania became an EU member state it is due to finally be allowed in the Schengen Zone. That might help make following my itinerary to the lost cities a bit easier. One thing that will not is the continuing legacy of Trianon. I sometimes wonder what my mentor’s colleague saw at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, perhaps the end of one world, and the beginning of a more insular one.

Coming soon: Magic Act – Subotica’s Starring Role (The Lost Cities #12)